- Why do we care about Housing?

- What goes up must come down?

- Look at Where We Are

- No equity in a college degree

Why do we care about Housing?

Property is the most expensive item most Americans will ever purchase. So, we will sacrifice a lot of additional spending to keep a roof over our heads. Observing the housing market is an excellent gauge of consumer confidence and financial health. It is integrated into nearly every economic sector and makes up a significant chunk of GDP (15% of GDP). The construction of new houses is, surprisingly, a small portion of the housing market, 3-5% of GDP. Rent and mortgage payments, then, make up 12-13% of GDP, as it is the most significant yearly expense of most households.

| Share of GDP | Description | ||

| Residential Investment | 3 – 5% | Construction of new structures; remodeling; broker’s fees | |

| Consumption Spending | 12 – 13% | Gross Rent & Utilities; Owners inputted rents and utilities | |

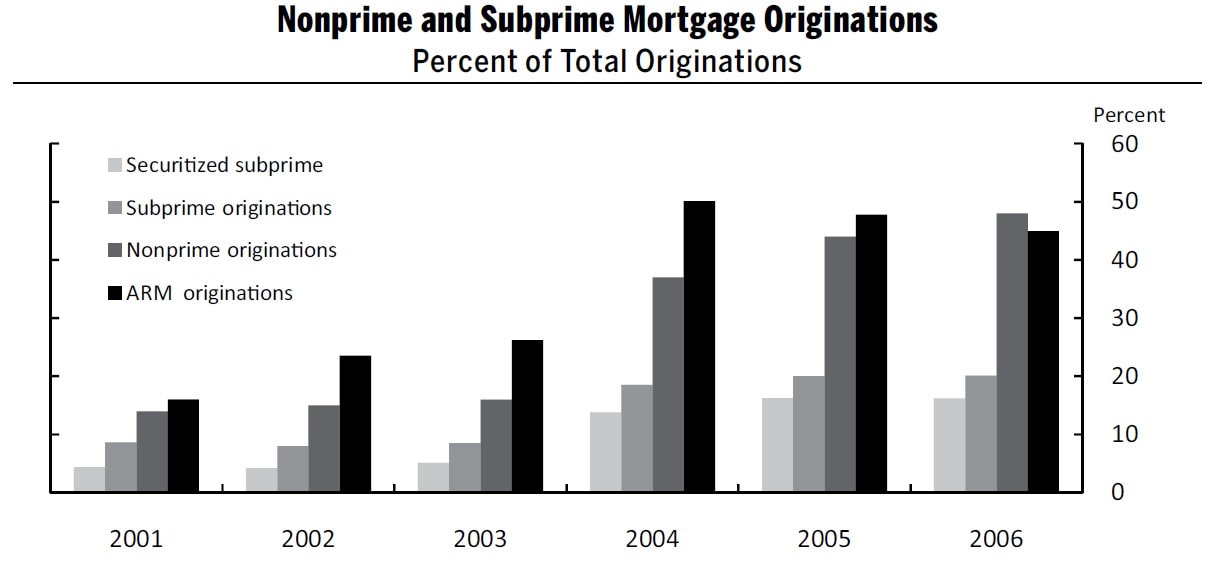

The 2008 Financial Crisis is unique because it involved the destruction of one of the United States’ most resilient industries. Neither the dot-com crash nor the 1997 Asian crisis dented the housing market. Usually, when home prices go up, people feel better off and feel more confident. Likewise, when house prices go down, people are more likely to cut down on spending and forego making personal investments. Home prices grew steadily from 1990 to Q1/2007 and, with them, people were looking for ways to make extra cash with the equity in their homes. So, refinance applications soared leading up to the crisis. Consumer confidence drove high borrowing and refinancing but adjustable-rate mortgages undermined the financial benefit and came back to bite owners (Indicated by those ominous black bars in Figure 1).

What goes up must come down

Funny enough, with home prices increasing steadily for over 10-years, people forget that whatever goes up must eventually come down. Maybe when investors are investing more in deteriorating mortgages, they cross their fingers and hope for the best. Regardless, these entrenched expectations of housing appreciation met low-interest rates and financial innovation to push home prices up at an accelerated rate after 2003. So, with a little financial invention, subprime and non-prime mortgage origination jumped in 2004, and the share of junk mortgages in mortgage-backed securities increased until it reached 80% in 2005 and 2006.

Home prices grew outside the United States, but it was the financial innovators who “built an inverted pyramid of leverage on the narrow fulcrum of ongoing domestic home-price appreciation” (Obstfeld and Rogoff).

Six million Americans lost homes during the Great Recession, and it takes a long time to rebuild that credit shock. As these Americans reenter the market, their wages have barely kept up with inflation and increased competition, from Millennials, is crowding the market.

Look at Where We Are

This month, August, the average rate on a 30-year fixed loan hit a 3-year low, 3.6%. Refinancing applications are up 12% at the beginning of August. Both metrics indicate a healthy housing industry and expectations that the good times will keep on rolling. Yet, while the situation is very similar to 2007, there isn’t the same level of risk. The weaknesses are more nuanced, and the links which make the housing sector a sound economic indicator are deteriorating.

There will not be a mortgage crisis anytime soon because new home buyers, millennials, are not traditional consumers. Millennials value flexibility, they marry later, and debt binds them more than any other generation. So, the industry will not have the gas to spin out of control. Millennials will reach financial maturity having witnessed the economic crisis affect loved ones, and that risk aversion is tough to shake – an availability heuristic.

Investors are starting to make up a higher percentage of home sales – at an all-time high and concentrated in lower-end markets. Private equity firms, like Blackstone Group Inc., bought loads of foreclosed properties after the crash and rented them back to the disgraced former owners. Investors concentrate purchases in high-growth areas, and these areas see less demand and slower price growth compared to regions without property investors. So, this investor activity may give additional stability to the market, if properly leveraged – albeit it creates problems for renters unable to buy their own home.

No equity in a college degree

Not only is debt a problem, post-college wages are persistently stagnant and the rise in contract labor are challenges for financial planning. Homes are 39% more expensive than 40 years ago and, despite low interest rates, buyers are priced out of rising houses because incomes have not increased with the price of houses. The mortgage crisis of 2006 seems to be impossible to repeat because people can’t afford homes or must save to reduce debt – making investing in mortgage-backed financial instruments more secure.

Low mortgage rates and high employment should make a healthy housing market, but the opposite is most likely the case. Entry-level homes are in short supply, as shown in Figure 2, because of competition from Millennials and investors burned by 2008 foreclosures, which have now rebuilt their credit. A repeat of the mortgage crisis is unlikely mainly because of restrictions on financial instruments and lending. The housing market, though, shows how wage stagnancy and household debt remain barriers to the pursuit of a culturally-iconic American investment.

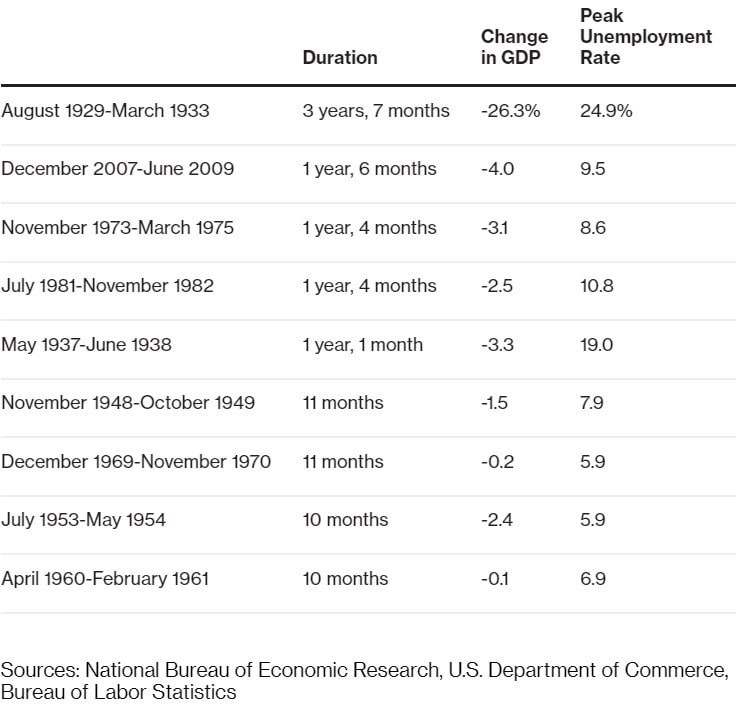

Marketplace analogized the likelihood of another recession as rolling a 6-sided die – eventually, the wrong number will come up. Economists suggest a 1-in-3 chance that the U.S. economy will shrink next year. Sure, another recession will happen eventually, but the devastating effect of the last financial crisis has led us to expect the next recession to be just as bad. This is not necessarily the case, and there is little evidence to suggest recessions match the magnitude of the expansion period. Recessions have a history of varying durations and employment severity (Figure 3).

The leveraging instruments that kicked the housing market into overdrive are not present today. But that doesn’t mean that every debt market is free from such systemic risk. In Part 1, I touched briefly upon the corporate debt crisis, and Part 3 of Recession Deja Vu will continue this risk narrative. You can follow this series and learn about our Financial Planning Software on our blog, investingcounterpoint.com, and don’t forget to signup for our newsletter.

Figure 3- Most recessions do not have the same duration or unemployment effect as the Great Recession and the Great Depression

Essential Reference: Maurice Obstfeld and Kenneth Rogoff’s Global Imbalances and the Financial Crisis: Products of Common Causes

Pingback : Recession Deja Vu - No Smoke Without Fire -

Pingback : Tenuous At Best IMF Reveals A Sluggish U.S. And Eurozone Buoyed By Emerging Markets -